This post is the final one in a series on anti-racist practice and Montessori education, adapted from a recent presentation I gave to the Bristol Early Years Forum for Anti-Racist Practice. In my first post (which you can read here), I explored how Montessori education, while rooted in radical principles of child liberation, can also be used to uphold systems of privilege and power. In the second post (linked here), I looked at the impact of systemic racism on my classroom dynamics. And in the third post (see here), I explored the importance of centering children and communities in this work.

In this final piece, I want to share some initial ideas for what a systemic, anti-racist response to such systemic problems might look like.

The Say-Do Gap

In 2019, I helped set up a Montessori adolescent programme at a large and demographically diverse charter school in North Carolina, where more than half the students identified as Black, Asian, or Latinx, and many families actively chose the school for its inclusive, community-oriented ethos.

At the school, there was a common narrative that families of color felt welcomed and safe—that this was a place they were choosing and loved. The school proudly held this up as a defining strength. But how did we know this was true? What data supported it?

When we eventually began collecting feedback through surveys and listening sessions, we discovered something very different. Some families were feeling left out or alienated. The systems we had assumed were working well were, in reality, excluding and confusing for many.

This kind of honest, data-driven self-reflection helped us confront what Elizabeth Slade of Public Montessori in Action calls the "say-do gap," —the space between what an institution claims to value and what it actually does. By facing the reality of those gaps, we could begin to move toward the school we wanted to be: a truly inclusive community.

📢 A big shout-out here to

, who helped spearhead much of this work at our school, and who recently presented on these issues in his talk "Fostering Equity: Cultivating Inclusive School Environments" at The Montessori Event and the Let’s Talk Racism Conference in NC 📢To quote

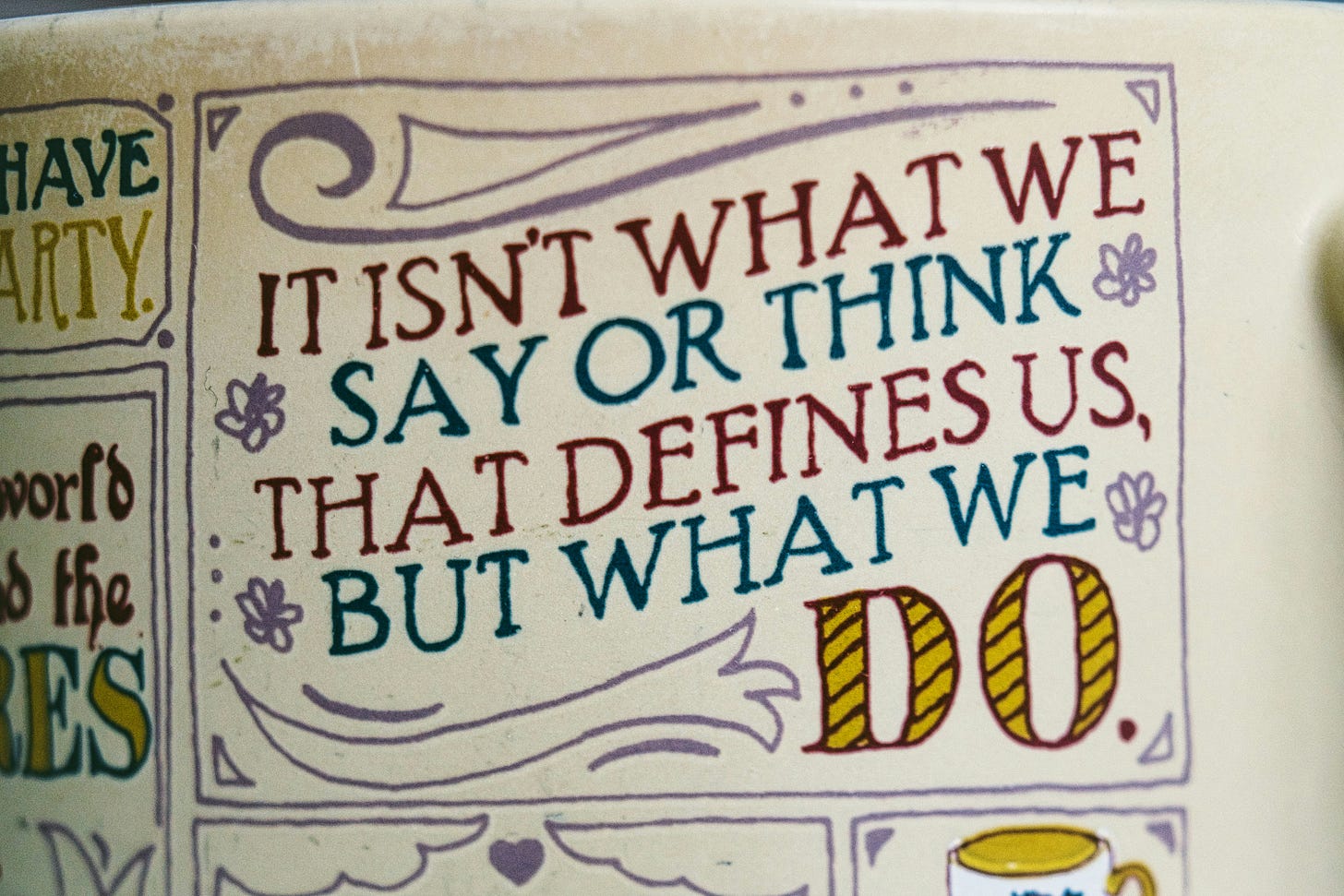

’s favorite coffee cup:"Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced."

—James Baldwin

A Collective, Systemic Response

Systemic problems require systemic responses—ones that are collective, sustainable, and comprehensive. This is not work that can be done by one teacher or one leader alone. It requires long-term commitment, collaboration, and accountability across the whole community.

As Britt Hawthorne writes:

“In Montessori education, just like in any other educational spaces, we’re novices in this work…

I don’t think that people really realize where the starting line is, that it’s so far back because for so long, we have not done work on a systemic level. So, whatever our solution is, it has to be systemic, and it has to be comprehensive.”

Britt Hawthorne from Equity Examined (2023).

I talk about such an approach in more detail in this article:

Equity: A Whole School Approach

This is the third article in a series on Elizabeth Slade’s book Montessori in Action: Building Resilient Schools written for Public Montessori in Action International. You can read the initial article here and the second article here. In this post, I look at the second “Core Element” of Slade’s “Whole School Montessori Method” - Equity. The post was ori…

But here are a few things your school can do now to start this work:

Conduct an Equity Audit – Establish a clear baseline for where your school stands in terms of equity. This could be a self-assessment or facilitated by an external ABAR facilitator.

Committee Work – Set up a DEI (or EDI: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) committee that includes teachers, leaders, parents, and students. Meet regularly to review school practices and push for more equitable approaches. At our school, we also developed JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) groups for adults to reflect on their own biases and identity work.

Equality Statements – While sometimes dismissed as performative, a strong equality statement can be a powerful starting point—publicly affirming your values and beginning to hold your community accountable to them. See, for example, this great work from AMI USA.

Collect Data and Question Assumptions – Gather qualitative and quantitative data—anonymous feedback from families and staff or academic data across demographic groups—and use this to identify and address patterns of inequity.

This Work Is for All of Us

When I’ve shared stories from my time in US schools to folks in the UK, people here often respond with, “Wow, it’s so different from the UK.” And weirdly, that’s been a pretty consistent response. People like to claim a sort of special status for the UK as a multicultural society.

Everyone wants to believe that racism is something that happens elsewhere—in the U.S., up north, or in London—but not in my liberal town or city. Not in Montessori schools. Not in my school. Not in my classroom.

But the dynamics I’ve described in my school environments are not unique to my setting. They are representative of all school environments.

A systemic or structural approach to anti-racism begins with the understanding that no one is immune from racism and bias. If we think it isn’t happening in our communities, it likely means we’re not paying close enough attention.

Ultimately, the work of becoming an anti-racist educator is an ongoing journey. Anti-racism is not a destination. There is no such thing as a fully anti-racist classroom. And I definitely don’t claim to have figured it out.

This is a dynamic and imperfect process—but one we are called to engage in all the same.

Congrats on your 50th post. They just keep getting better! Especially when you give me a shout out 😆.