Montessori as a Colonizing Force

Are We Truly Liberating Human Potential, or Are We Perpetuating Systems of Oppression?

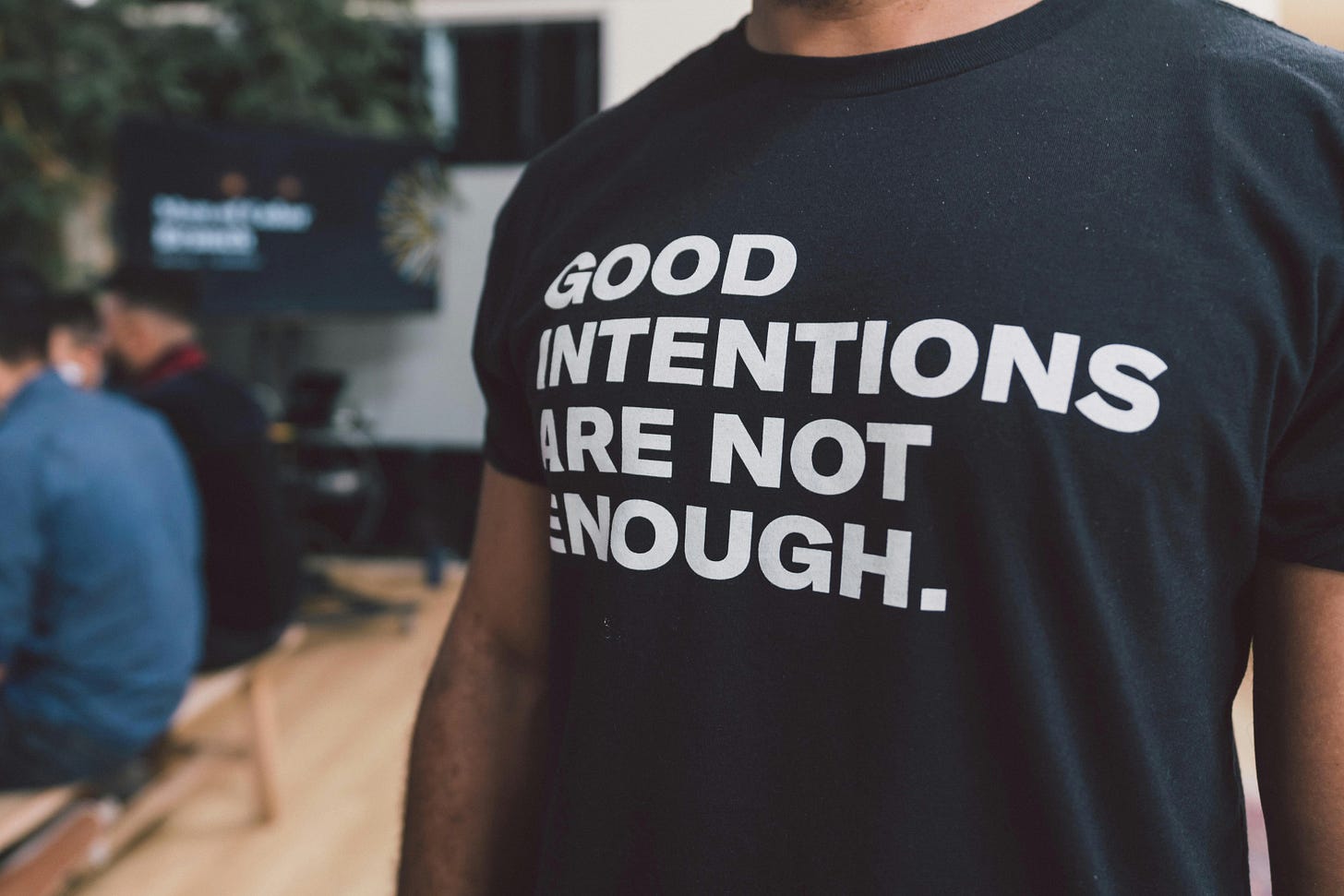

The Greatest Harm Can Result From The Best Intentions

A friend who works in festival safety recently told me about an incident with a fire warden who jumped a barrier to rescue someone being crushed in the crowd. Although his impulse to save someone was honourable, ultimately, the fire warden’s actions went against safety protocol and he caused more serious injuries due to the added crowd pressure he created.

As Montessori educators, we often see our work as inherently just, inherently good. Yet, history shows us that even the most honourable, progressive ideas can become tools of oppression and harm when implemented without a critical lens. Anti-racist education requires not just good intentions but a systemic and sustained effort to challenge inequity at every level.

In my journey as an educator, I’ve come to understand that working toward an anti-racist practice requires grappling with a lot of complexity and discomfort. It means reckoning with the historical and social contexts that shape our schools, as well as the unintended consequences of well-intentioned reforms.

The Complex Reality of Public Montessori Schools

Years ago, I joined a state-funded Montessori school in an urban district in the U.S. South. Originally a neighbourhood public school, it had been transformed into a magnet school a decade earlier. This transition was seen as a huge success—how lucky we were to have a local, publicly-funded Montessori program!

From the 1970s to the early 2000s, U.S. public school districts introduced magnet programs in an effort to reintegrate schools. These schools, which offered specialized curricula like Montessori or Dual Language Immersion, were marketed as models of “school choice” within the state system—promising high-quality education within diverse communities to attract white, middle-class families back to city centres.

And it worked—the student body at my school had certainly been reshaped:

Before becoming a magnet, over 80% of students at my school were Black, and 90% qualified for free lunch. By 2017, when I worked there, the student body had shifted to 21% Black, 37% white, and 35% Hispanic. By 2023, it was 60% white, 18% Hispanic, and 12% Black, with only 27% of students qualifying for free lunch.

This transformation wasn’t limited to who attended the school—it reshaped the surrounding neighbourhood. The transition to a Magnet school also contributed to the gentrification of local neighbourhoods and the displacement of Black and Brown families from both the school and surrounding areas. Although admission to the school was through a lottery, meaning that technically anyone could apply, families who lived within the roughly 1-mile area around the school were given priority over those who didn’t. As a result, real estate agents marketed proximity to the school as a selling point, driving up home prices and accelerating the displacement of long-time residents.

As property values and rent prices in the surrounding neighbourhoods rose, higher property taxes and housing costs made it increasingly difficult for Black and Brown families to remain, shrinking their presence in both the school and the community it was meant to serve. Alongside the students, Black and Brown teachers also disappeared, further eroding the representation and cultural continuity that once defined these schools.

As a white teacher entering this environment, I was a reflection of the very displacement that had reshaped its community. This situation was especially hard to swallow as someone who had joined excited to work at the intersection of Montessori and public education.

Are Montessori Schools Living By Their Values?

I hope this story serves as a provocation to Montessori educators who would assume that Montessori education serves as an uncomplicated force for good. We could all have a little bit more humility when talking about “mainstream education” (myself included). And public Montessori educators who believe their work is in some way morally superior to private Montessori schools should also check their privilege.

Montessori is predominantly a private school model, and even in public Montessori schools access is limited—most programs exist within magnet or charter schools, both tied to the problematic politics of school choice. Many Montessori schools have unintentionally become forces of segregation, gentrification, and exclusion—caught up in their own reformist zeal. Mira Debs’ book Diverse Families, Desirable Schools is required reading for anyone in the Montessori community willing to face this complexity.

For those committed to anti-racism in education, these dynamics raise essential questions:

How do we understand the history we are inheriting in our schools?

How do we recognize the role we play in reinforcing, or resisting, these patterns?

And how can we move beyond surface-level diversity to address deeper systemic inequities?

What Can Schools Do?

What if Montessori schools reframed their role to actively dismantle privilege rather than reinforce it?

The very existence of private institutions, magnet, and charter schools, especially those with high tuition fees or limited access, raises questions about their impact on social justice.

How do these schools contribute to social stratification?

Do we see a significant lack of diversity, either in terms of race or class?

Do we unintentionally create a ‘safe space’ for the privileged while excluding those who most need educational alternatives?

Here are some ideas for how schools might start addressing these issues of systemic inequity in their communities:

Reflecting on the Role of Private Institutions: How does your school account for the harm it may unintentionally cause? Are you actively working to reduce barriers to access through scholarships, sliding-scale tuition, or other means? What if Montessori schools reframed their role to actively dismantle privilege rather than reinforce it?

Collaborate with Local Schools: Does your school collaborate with local public schools in ways that genuinely contribute to educational equity? Rather than existing in isolation, Montessori schools could build partnerships with public schools—sharing resources like professional development, teaching materials, or extracurricular spaces. Such collaboration could help counteract the gentrification effect Montessori often brings.

Actively Addressing Gentrification and Displacement: In areas with rising property values, how can Montessori schools avoid contributing to displacement? What strategies can be put in place to ensure that local families, especially those who are historically marginalized, can continue to benefit? Schools might explore affordable housing partnerships, community programs, or prioritizing local families in admissions policies.

Reaching Out to Underrepresented Families: How can schools widen access to marginalized families, particularly those from Black, Brown, Indigenous, and low-income backgrounds? A genuine commitment to anti-racism requires institutions to make a tangible effort to include underrepresented groups and actively recruit diverse voices. It’s not enough to just welcome diversity; Montessori schools need to seek it out, intentionally creating pathways for families who might otherwise never have access to a Montessori education.

Expanding the Scope of Diversity: Moving beyond surface-level diversity is essential. It's not enough for schools to enrol students from different racial backgrounds if the educational experience still prioritizes white, middle-class norms. Montessori schools should invest in developing curricula and practices that reflect the lived experiences of students from various cultural backgrounds, not just superficially, but in ways that affirm and empower their identities.

Hiring for Equity: Representation matters. What steps are you taking to hire and retain a diverse teaching staff? Schools must prioritize equitable hiring practices and support educators from marginalized backgrounds. Training in anti-bias education and providing leadership opportunities for diverse educators are essential for fostering an inclusive, anti-racist environment.

And if your school has a predominantly white student and staff body, your responsibility to address these issues is even greater!

By engaging with these ideas, Montessori schools—whether private or public—can begin to shift the narrative from being passive participants in systems of privilege and colonization to active agents in creating a more equitable and inclusive education system. If Montessori truly seeks to liberate human potential, it must grapple with these hard questions and shift from well-intentioned to systemic, sustained action.

Great piece! What you described at your school is consistently happening across the country in public Montessori schools. Do you (or anyone) know of schools or districts we can look to who would be a model for bucking this trend? What Durham Public Schools in NC is doing right now may be a viable option but time will tell.

Fascinating, thank you so much for this insightful piece.