Credit to Kimberley Cooper of ThriveNow Education, who first brought this report to my attention.

In January 2025, the World Economic Forum published its latest Future of Jobs Report. It projected that by 2030, rapid advances in AI, automation, green technologies, demographic shifts, and ongoing global uncertainty will result in the displacement of 92 million jobs—but also the creation of 78 million new roles. These emerging roles demand entirely different skillsets—skills that our current education systems are barely beginning to acknowledge, let alone nurture.

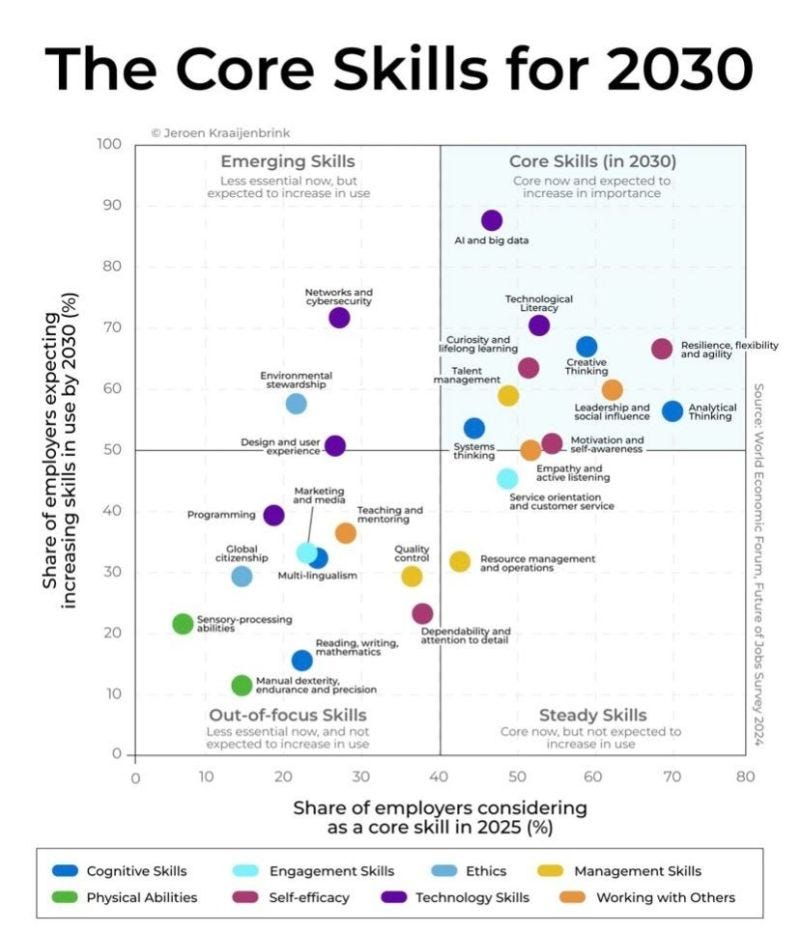

The graph above shows “key priority areas for workforce development,” comparing core and emerging skills by 2030 based on their relative importance today and how they’re projected to evolve.

There’s a lot to unpack in the graph, but at its heart is a simple truth: the future belongs to the curious, the adaptable, the emotionally intelligent, and the ethically grounded. Rising skills include:

Creative thinking

AI & technological literacy

Resilience, flexibility, and agility

Systems thinking

Empathy and active listening

Motivation and self-awareness

Leadership and social influence

Environmental stewardship

These are deeply human capacities—what the WEF report calls “human-centric skills.” They can’t be memorised. They can’t be taught through worksheets. But they can be cultivated through experiences that are real, relational, challenging, and meaningful.

And then look at what’s on the decline: reading, writing, and arithmetic. For over a century, the “Three R’s” formed the foundation of schooling and were once enough for most factory, clerical, or service jobs. Our entire education system was engineered to develop those skills—efficiently, uniformly, and at scale.

But the world has changed. The workplace has changed. And although schools claim GCSEs and the like prepare students for the “real world,” what remains is a generation of young people being educated for a world that no longer exists, in schools designed for a past that cannot return.

If we want to prepare children for the world ahead—not the world behind—we now need an educational approach that honours the full complexity of being human.

Explorer Mode

“Uncertainty is the new norm. No one knows exactly what shifts in jobs and society are in store. What can best prepare our kids? The only thing that can insulate them for rapid change and give them confidence to move forward is the ability to learn and adapt.”

—Rebecca Winthrop & Jenny Anderson, The Disengaged Teen

I’m still reading The Disengaged Teen: Helping Kids Learn Better, Feel Better, and Live Better, but I already know it’s going to be a must-read for secondary teachers and parents.

The authors describe this era in education as the Age of Agency—a time when young people must become resilient learners, not just repositories of knowledge. They highlight how this shift has long been visible in “alternative school models on the margins of education systems,” Montessori schools in particular.

In this Age of Agency, academic knowledge alone won’t be enough. Young people will need creativity, self-awareness, and the ability to generate ideas, build on old ones, and communicate them effectively.

They will need to become Explorers. As Winthrop and Anderson write, “Explorer Mode is where kids become resilient learners and build skills that help them thrive.”

“Exploring is not navel-gazing or prolonged wandering... It is not the developmentally important exploring toddlers do, which is aimless and joyful. Nor does exploring sacrifice achievement in school… The ability to engage deeply in learning, to have a say in how they spend much of their significant mental energy, is not a nice-to-have but a must-have. It is the price of entry for a meaningful life, whatever they choose that life to be.”

And how do we unlock Explorer Mode?

We prioritise agency. We prioritise engagement.

From Explorer Mode to Montessori

Maria Montessori was saying all this over seventy years ago. Her critique of secondary education was—and still is—devastating.

In From Childhood to Adolescence (1948), she wrote:

“It is necessary that the human personality should be prepared for the unforeseen.”

She argued that schools were already outdated in her time, remaining in “a kind of arrested development,” and “organised in a way that cannot have been well suited even to the needs of the past.” Education, she insisted, must move beyond rigid specialisation and rote learning, and instead cultivate flexibility, resilience, and moral courage.

“Adaptability—this is the most essential quality.”

Montessori envisioned a “school of experience in the elements of social life”—a setting where adolescents would gain not just knowledge, but purpose and agency. She believed that young people should be treated not as passive students, but as emerging citizens—capable of real work, real choice, and real contribution.

I’ll talk more about this seminal essay next week, and how it influences what we’re building at Lumiar.

Future Skills

So, what does a school and curriculum look like that actually prepares students for their future?

At Lumiar, learning is not preparation for life—it is life. Our school is a microcosm of the real world. Students learn through interdisciplinary projects, collaborative problem-solving, and authentic experiences. They practice leadership in circle time, develop empathy through collective decision-making, cultivate curiosity through self-directed projects, and build systems thinking and resilience by engaging with complex, messy challenges that have no single right answer.

Of course, this kind of education needs structure. It can’t just be good vibes and group projects. That’s why in our secondary programme, we use a framework that brings coherence to the messy, human-centred work of preparing for life: the Da Vinci LifeSkills Spiral.

This spiral maps 27 essential personal, social, and practical competencies—not in a fixed hierarchy, but as interwoven capacities that deepen over time. From inspiration to self-assessment, from empathising to resourcefulness, it gives us a shared language for what most schools ignore: how to be a whole human in a rapidly changing world.

At Lumiar, we use the spiral to guide formative assessment and reflection. Students learn to evaluate their own progress in conversation with mentors, using the skills spiral and its subskills as tools for feedback and growth. They also learn to give and receive kind, specific feedback with their peers, again using this shared language.

Rather than evaluating students for fixed academic outputs alone, we focus on skills and competencies—the learning behaviours that shape how, not just what, students learn. These skills are embedded in every project, every discussion, every day.

At Lumiar, we’re not just asking what students should know—we’re asking who they’re becoming.

Somedays I feel this change in thinking about education, which as you point out has been around for almost a century, is like the battle to stop smoking. We know a much better way, the necessary skills to support young people for their future and keep them engaged in learning, but we still default to outdated education models. Thanks for continuing to promote a better, different way. As I wrote in 2017, The World Needs More Montessori, linkedin.com/pulse/worl… and we need it more than ever.

I love everything I just read here. This school is doing what I’m dreaming. 💭 You mentioned a secondary program. That goes past age 14? I’m developing my philosophy on what to do with “high school.”