In the Dog House

At the beginning of November I publicly announced I’d be writing an article a day in recognition of NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). Now, I doubt anyone was following me too closely, but, if you were, you’d have noticed that I came out of the gate strong (Article 1, Article 2, Article 3 & 4, Article 5), and then abruptly pulled up around Nov. 12th.

Why, you ask? Well, this is why:

Say hello to Teddy, our now four-month-old Cockapoo, the latest addition to my family. We didn’t quite get Teddy on a whim; we always planned to get a dog upon moving to the UK. But let’s just say I was certainly much more prepared for NaNoWriMo than I was for a new puppy.

I had thought that now my son was seven and my daughter eleven, we were through the early parenting stage. Suddenly, I’m dealing with sleeplessness, potty accidents, whining, and teething all over again. Also this time, I’m most definitely mother. Teddy has imprinted himself on me, hard. I have a fluffy little shadow that follows me everywhere and cries whenever I so much as think about leaving the house. Safe to say, my writing has suffered.

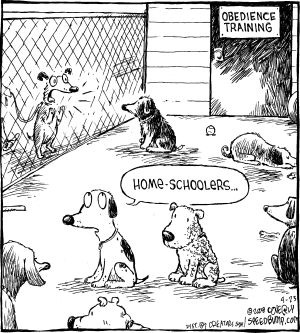

Of course, Teddy is also absolutely stinking gorgeous—I’m writing this with him sleeping on my feet, *loving sigh*. And, as with any new life choice, he’s been accompanied by a flood of new information and learning. In this article, I want to reflect on the world of dog training into which I’ve recently been inducted and, of course, all the ways it seems to connect with my thoughts about education.

The Progressive Education of Dogs

One of the first questions to answer upon getting a dog was: what training approach should we take? Tiger mom? French bébé? Attachment parenting?

Early on, I read this article from Time Magazine titled “How Science is Revolutionizing the World of Dog Training,” and it blew my mind. The article documents a paradigm shift in dog training from dominance and obedience-based methods to socialization, relationship-building, and positive reinforcement. This isn’t just a passing trend; it’s a radical shift rapidly adopted across all forms of dog training—including domestic, police, military, guard, and guide dogs.

Science has shown that the fewer negative approaches used in training—scolding, physical corrections, isolation, etc.—the more quickly a dog will learn. This has become widely accepted as common sense. The article states:

As canine training has shifted from the old obedience-driven model directed at show dogs to a more relationship-based approach aimed at companion dogs, trainers have discovered that the use of negative reinforcement and positive punishment actually slow a dog’s progress, because they damage its confidence and, more importantly, its relationship with a handler. Dogs that receive too much correction—especially the harsh physical correction and mean-spirited “Bad dog!” scoldings—begin to retreat from trying new things.

The speed of this consensus shift, happening over the last 20 years, is incredible. Honestly, it makes me hopeful. Why couldn’t a similar paradigm shift be reached in education? Science and common sense are on our side. It baffles me that this consensus has been reached in dog training, yet in most schools, we still use punishments with children to drive learning—despite the fact it goes against the science. Sure, we’ve moved away from corporal punishment, but sanctions, scolding, and exclusion still play a central role.

The article identifies some keys to why this paradigm shift has happened and what we can learn to help enact revolutions elsewhere:

Behavioural science backs it: “Dogs from the positive schools universally performed better at tasks the researchers put in front of them, and the dogs from aversive schools displayed considerably more stress, both in observable ways—licking, yawning, pacing, whining—and in cortisol levels measured in saliva swabs.”

It is more effective and expedient: "Over the past 15 years, handlers with Guide Dogs for the Blind ... have extinguished nearly all negative training techniques and with dramatic results. A new dog can now be ready to guide its owner in half the time it once took, and they can remain with an owner for an extra year or two."

Old myths have been discredited: “The origin of so-called “alpha theory” [upon which the old, dominating, Cesar Millan–style methods were based] comes from a scientist named Rudolph Schenkel, who conducted a study of wolves in 1947 in which animals from different packs were forced into a small enclosure with no prior interaction. They fought, naturally, which Schenkel wrongly interpreted as a battle for dominance. The reality, Schenkel was later forced to admit, was that the wolves were stressed, not striving for alpha status.”

I also feel like it is easier to overcome the complex knot of bias in our relationships with dogs than it is with children. We can more quickly dispel the myth of the “bad dog” than that of the “bad kid”. Sure, dog training still has its own culture wars: there are still some advocates of aversive methods, and some people who lament the wokification of dog training, but overall it seems that we have reached a degree of cultural clarity and consensus that I find inspiring.

Dog Parenting

I recently read that the key difference between training dogs and raising children is that with children, we work towards functional independence, while with dogs, we expect them to be dependent on us their entire lives. They’re not going to pack a lunch, head to school, or walk out the door to work one day.

Although there are critical differences, I think that training a dog would be a great prerequisite for raising a child or becoming a teacher. The fundamental skills needed for being successful are very similar - consistency and routine-building; being authoritative, patient, and calm; investing in relationship-building; focusing on socialization; and observation of behaviours and needs. In many ways, training Teddy has helped remind me of some of the fundamentals I should be using with my own children.

Here are a few of my key takeaways:

Be authoritative: Dogs give such great feedback to their owners. They respond to confident, calm, assertive commands. If you dance around repeating “down”, “down”, “down”, “down”—they won’t listen. Clear, firm, kind, relationship-centred leadership with consistently enforced boundaries and expectations is key. I love this trainer Will Atherton and his idea of being a “loving leader” to your dog. This is the positive discipline approach. You have to be both highly responsive and highly demanding in equal measure.

Consistency and routine matter: Dogs and children thrive on consistency and routine. Puppies quickly teach you the value of routine—without it, you get accidents, whining, and nipping.

The skill of observation: Because we can’t talk to dogs, we have to carefully observe their behaviour to be tuned into their needs. If your dog is panting or yawning, that is an indication of stress. If they are circling near the door, they need to go out and pee. If their tail is wagging, they are having a great time. Being able to tune into another being’s needs is the key to great teaching and parenting.

Exercise and play are critical: When dogs exhibit negative behaviours, they often need exercise or stimulation. Similarly, children need to move and play to thrive. If we keep them cooped up, what do we expect?

Calm leads to calm: If you’re calm and confident, your dog will be too. It’s a great reminder to regulate yourself first.

The limitations of rewards: You quickly learn that rewards have to be used judiciously, otherwise, you get into an expensive arms race with the dog and treats stop having an impact.

Prioritize socialization: Dog socialization is the process of exposing a puppy, particularly during the critical period from 8 to 20 weeks, to a wide range of people, environments, objects, and situations they might encounter later in life. Proper socialization helps prevent fear-based behaviours and ensures that dogs are comfortable and confident in diverse circumstances. For children, socialization prepares them for a complex world.

Adopt a no-blame culture. You can’t really blame a dog for their behaviour. If something’s off, it’s on the owner. Parents and teachers could learn from this mindset, focusing on how environments shape behaviour rather than assigning blame.

New Tricks

So, while my NaNoWriMo goals may have fallen by the wayside, Teddy has taught me lessons I couldn’t have learned otherwise. Whether it’s about education, relationships, or just finding joy in chaos, this little ball of fluff has been worth every sleepless night and piddled-on carpet. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a puppy to walk.

As a mom and a dog (and a cat) mom....yess!! 💖 Dogs are great teachers, and great kids and pupils too. My Tibetan Spaniel is not really the *obedient* type, but he is indeed a darling and raising him from a puppyhood prepared me well for the role of a mom to small humans. 🐶

Great read! Thanks for publishing.